Soon after, Columbia Records released Dylan's seventh studio album the double disc, 'Blonde On Blonde'. I say soon after, for the actual release date of the album is rather vague. Most put the date as 16 May 1966, the day before the infamous Manchester concert. However, that date is disputed by writer Michael Gray who claims in his 'Bob Dylan Encyclopedia' that the album was not readily available until June or early July. In the UK, the album was released and charted in August 1966.

Whatever the date, it would certainly be one of the first, if not the first double albums in rock/pop history. (It vies for that accolade with 'Freak Out!' by The Mothers of Invention, which was also issued in June 1966). It also continues the development of Bob Dylan the rock musician as opposed to Bob Dylan the protest folk singer. Having released an album 'Bringing It All Back Home' in March 1965, on which he played one side of rock'n'roll songs backed by amplified, electric instruments, he then caused something of a furore at the July 1965 Newport Folk Festival when he donned an electric guitar and was backed by members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Not content with that, in August that year he released his first fully-fledged rock album, the incendiary 'Highway 61 Revisited'. Don't go thinking that it was only the loud raucous music that offended his folk-purist fans, for the lyrics also were far removed from anything Dylan had done previously. In fact they were far removed from anything that had gone previously! It was rock'n'roll and poetry fused as one!

So effectively, aside from being a double album, 'Blonde On Blonde' did not come as so much of a shock. Even the inclusion of 'Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands' which clocked in at over eleven minutes and took up all of side four of the album, was not totally new. The previous album had included 'Desolation Row' which was almost identical in length. What really set 'Blonde On Blonde' apart from its predecessors, was the sound. It was what Dylan himself described in 1978 as 'That thin, that wild, mercury sound. Metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up'. Bob Dylan had completed the journey from folk hero to electric messiah.

The recording sessions began on 5 October 1965 at Columbia Recording Studio A in New York with members of Dylan's touring band, The Hawks (soon to be renamed The Band). Further attempts were made in the same studio on 30 November, then on 21 January 1966, 25 January and 27 January, the latter two sessions with a slightly different line up of musicians. From these sessions, only one track 'One Of Us Must Know (Sooner Or Later)' made it onto the released album.

Recognising that Dylan was dissatisfied with his attempts to record in New York, producer Bob Johnson suggested a move to Nashville where they could utilise Nashville session musicians. Despite objections from Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman, Dylan agreed and the first session took place at Columbia Studio A in Nashville on 14 February 1966. They continued for three days and then possibly reconvened for three days between 7 and 9 March. I say possibly because musician Al Kooper has disputed the fact that there were two blocks of sessions in Nashville. It was also suggested that the musicians present were not kept fully occupied and sat around chatting and smoking while Dylan laboured on his own attempting to complete the lyrics to his satisfaction.

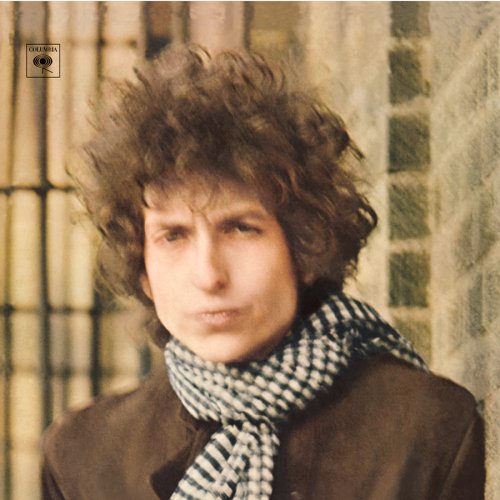

The released record came in a gatefold sleeve with a slightly out of focus photo of Dylan spanning the front and back covers. Neither his name, nor the album title appeared on early copies. Wrapped in a double breasted brown suede jacket with a checked scarf thrown around his neck, he stares unsmiling into the camera, his face framed by a mop of wild, unkempt brown hair. Aside from the serious expression, he could hardly have looked more different from the grainy image of the young man in a work shirt that adorned the front of 'The Times They Are A-Changin'', from three years before. As he had predicted, the times had indeed changed.

There's a party going on, or so it seems in album opener 'Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35'.

Kenny Buttrey announces the shenanigans with his drummed intro before Dylan's harmonica, the trumpet of Wayne Butler and trombone and tuba begin this joyous melody. According to Dylan, 'everybody must get stoned' and on this recording it seems that they are all having a great time; hell even Dylan can't even stop himself from laughing. It's an infectious opener which was recorded on the evening of March 9 and into the following morning.

It's down to earth with a bump for 'Pledging My Time' which is a slow, pulsing 12 bar blues song. Opening with Dylan's harmonica, the blues feel continues thanks to guitar from Robbie Robertson and rolling piano chords from Hargus (Pig) Robbins. Lyrically, the meaning of the song is ambiguous but it is not uplifting. Strangely for some reason, the mono UK version is about ten seconds longer than the version issued in the US.

Acoustic guitar and wailing harmonica introduce the next song before Dylan delivers that classic opening line 'Ain't it just like the night to play tricks when you're trying to be so quiet'. 'Visions of Johanna' then takes us on a journey through places where 'the heat pipes just cough' and introduces a host of strange characters. Much has been written about the apparent meanings of the song but one theory suggests that it came about during a power blackout that took place on 9 November 1965. The original title 'Freeze Out' tends to support this, as do lines such as, 'lights flicker from the opposite loft', 'we sit here stranded', 'the heat pipes just cough' and of course, 'there's nothing, really nothing to turn off'. Nevertheless the finished song seems to be more concerned with atmosphere rather than specific meaning. In that respect, it works. 'The ghosts of electricity howl from the bones of her face'. Indeed!

Originally recorded as a more uptempo song during the New York sessions, Dylan eventually settled on the released version where he was superbly backed by guitarist Charlie McCoy, Joe South on bass, Kenny Buttrey on drums and Al Kooper on organ.

'One Of Us Must Know (Sooner Or Later)' is the only song that survived from the New York sessions. It stands apart from the other songs in that it lacks that metronomic drumming of Kenny Buttrey, but the album would definitely be weaker without this glorious song. Against the shimmering organ of Al Kooper and Paul Griffin's piano lines, Dylan joyously releases his feelings of guilt, bitterness and loss. Addressing the woman with whom he thought he had an 'open' relationship, he apologises for having hurt her. 'And I told you, as you clawed out my eyes that I never really meant to do you any harm'.

And so ends side one of the original long playing record.

Side two opens with Dylan addressing the new object of his desires in 'I Want You'. However far from being a straight forward declaration of desire, in this short bouncy tune, Dylan introduces us to another host of weird and wonderful characters including a guilty undertaker, a lonesome organ grinder and a dancing child who some commentators state may refer to Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones. Recorded at the final Nashville session, this song is the shortest on the album at just over three minutes and was appropriately issued as a single in June 1966. Incidentally, this song was almost ten seconds longer on the mono UK version than the US version.

It is followed by the equally bouncy 'Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again' which was just called 'Memphis Blues Again' on the original album. What a wonderful piece of programming to have these songs follow each other as they complement each other perfectly. Despite being another song that is impossible to decipher the true meaning, the effect of the song is uplifting. Just listen to how Buttrey drives the rhythm and Al Kooper fills the few spaces with those wonderful 'wild mercury' organ fills. This was the only song to be worked on during the 16 February Nashville session and took twenty takes to complete.

'Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat' is track three on the second side of the record. Whether the structure of this song was borrowed from Lightning Hopkins is open to debate but nevertheless it is a rollicking, romping blues that may or may not be about the model and aspiring actress, Edie Sedgwick. Despite being a relatively straight forward blues, it still took thirteen takes to complete. The mono version in the UK was for some perverse reason slightly shorter than the US version.

The first disc closes with probably the most commercial song on the whole album, 'Just Like A Woman'. Even those who don't like Bob Dylan tend to like this lilting love song. Recorded at the 8 March Nashville session, the recording features beautiful nylon strung guitar from either Joe South or Charlie McCoy, piano from Hargus Robbins and distinctive organ from Al Kooper. Robbie Robertson was present at the session but did not play on this song.

Side three of the album is in some ways the weakest side as the songs tend to be less strong, yet they emphasise how well the sequence has been programmed as the five tracks work very well together. Beginning with 'Most Likely You Go You Way (And I'll Go Mine)' which with it's brass accompaniment and it's moderate blues tempo echoes the album opener, the side continues with 'Temporary Like Achilles', a slower piano backed blues number. These appear to have been recorded in this sequence in Nashville on 9 March 1966. In my view, these 'lesser' songs sound punchier and better in the original mono mix rather than stereo.

The centrepiece of side three is another uptempo number 'Absolutely Sweet Marie' which is yet another song difficult if not impossible to interpret. The melody appears to have been stolen by Steve Harley for his number 1 hit 'Come Up And See Me (Make Me Smile)'. This was the only song recorded at the session on 7 March 1966 although it is likely that the musicians were assembled then, though the actual recording may not have commenced until the early hours of the following day.

'4th Time Around' was recorded in several attempts on 14 February 1966 and seems to have been the first song worked on after the move from New York to Nashville. However it appears that harpsichord and drum overdubs were added as late as 16 June which would appear to support Michael Gray's theory that the album was not released in May. Whether these overdubs were actually used in the final recording, is open to debate.

A beautiful melody with rolling, circular acoustic guitar accompaniment, this song has often been cited as a reply to The Beatles 'Norwegian Wood' which they recorded for their 1965 album, 'Rubber Soul'. This John Lennon song had clearly been influenced by Dylan himself so Dylan may have been paying a homage to Lennon or, as Lennon interpreted later, it may have been a warning not to use Dylan's ideas. Lyrically the song appears to begin in the middle of an argument between a pair of lovers. It begins, 'When she said "Don't waste your words, they're just lies" I cried she was deaf'. Musically this is the strongest track on side three and stands out as being different to anything else on the album.

'Obviously Five Believers' suffers by comparison to the previous song. A straight forward, rocking blues, it was recorded at the same session that provided the opening tracks from this third side. In my view this track sounds far better in mono than in stereo where the instruments are too widely spread and consequently the song seems to rock less.

Flip the second disc over to side two (the fourth side of the album) and you find only one track, the eleven minute plus 'Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands'. Recorded at the end of the 15 February session, the song was actually written there and then in the studio. Apart from three earlier takes which were little more than rehearsals, the backing musicians had no idea what to expect from the song. Kenny Buttrey explained that the band continued to peak at the end of each verse, thinking that they were reaching the conclusion of the song.

That does not occur until 11 minutes and 23 seconds have elapsed. In a song of that length, there is a lot to analyse and many attempts have been made to reveal the true meaning. Initially Dylan declared it the best song he had written but three years later he said that he just kept writing and couldn't stop despite forgetting what he intended to write about.

The album was generally well received by music critics although some claim that like The Beatles double album (The White Album), it was perhaps three quarters of a superb album. It reached the top ten in both the US and the UK completing that famous trilogy of 'electric' albums began in the spring of 1965.

On 29 July 1966, Bob Dylan fell off his Triumph Tiger motorcycle near his home in Woodstock. The extent of his injuries were never fully revealed and no ambulance was called to the scene but nevertheless, Dylan went into a period of seclusion. This lasted over a year during which time he made some basement recordings with The Band but he did not emerge into the recording studios in Nashville until October 1967. This time, the results would be very different.

No comments:

Post a Comment